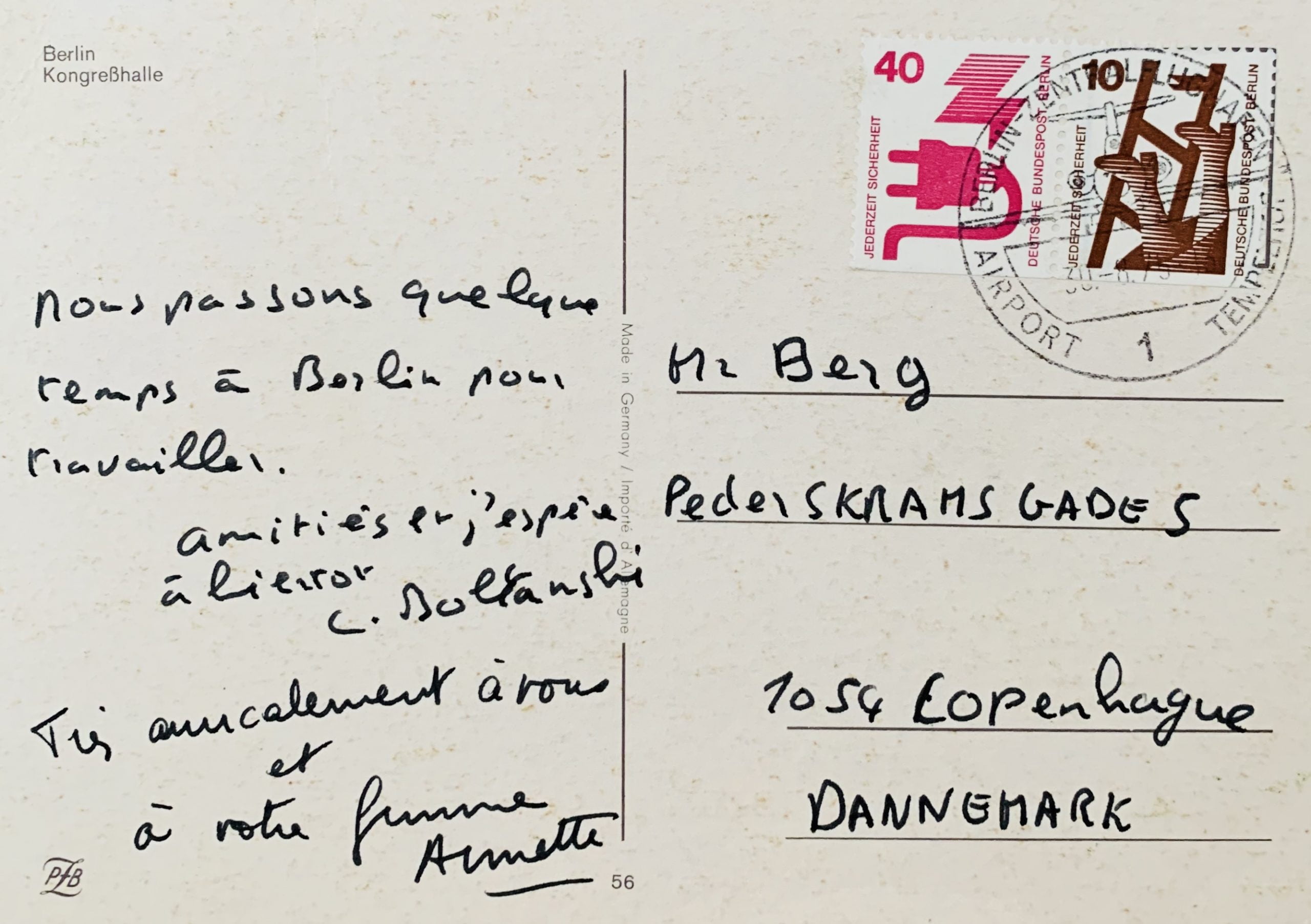

Photo – Christian Boltanski with Paul Robertson in 2016

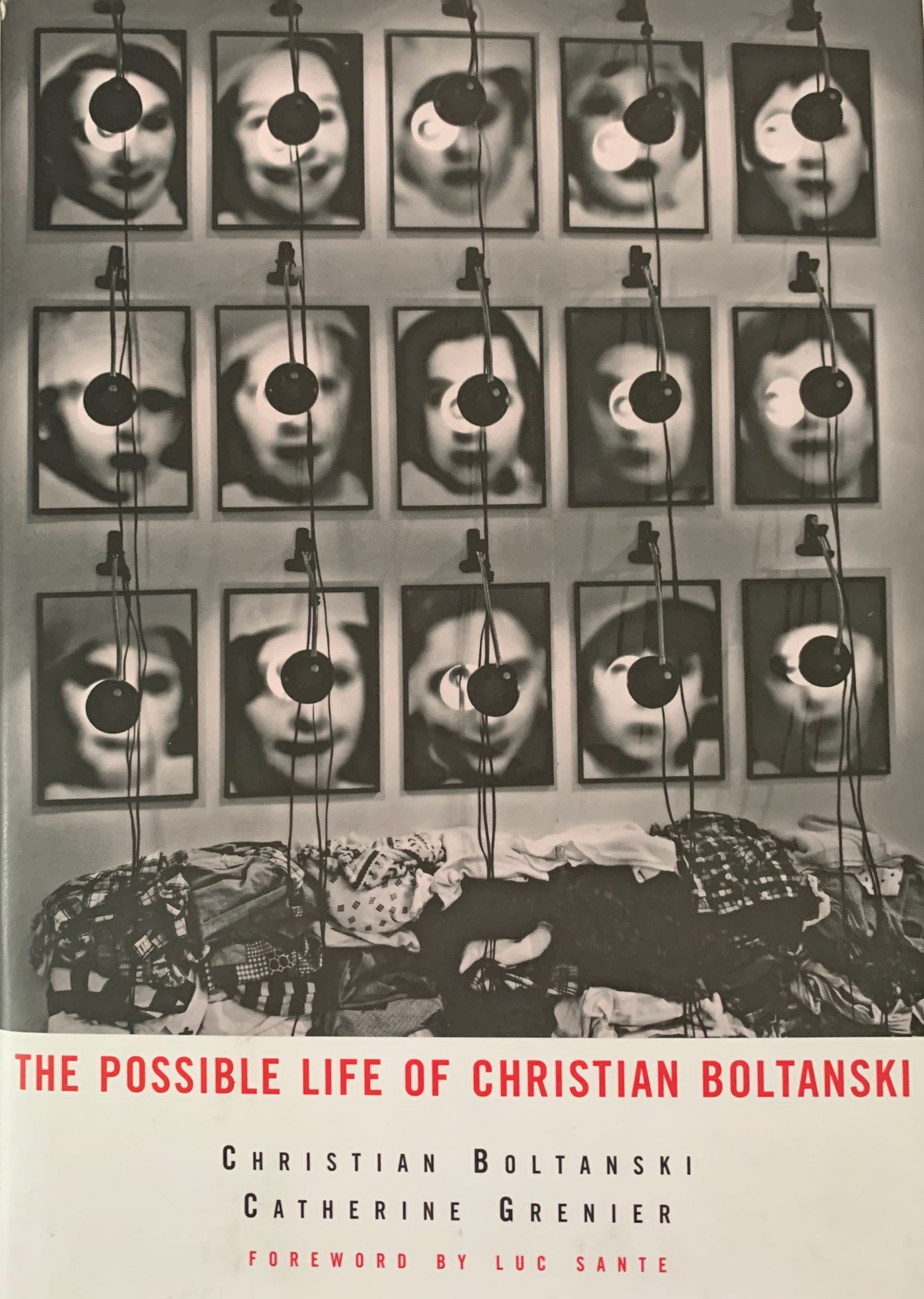

Born in 1944 in Paris immediately after the war of a Catholic mother and a father who had converted from a Jewish heritage, Christian Boltanski was arguably one of the greatest French artists. He died in July 2021.

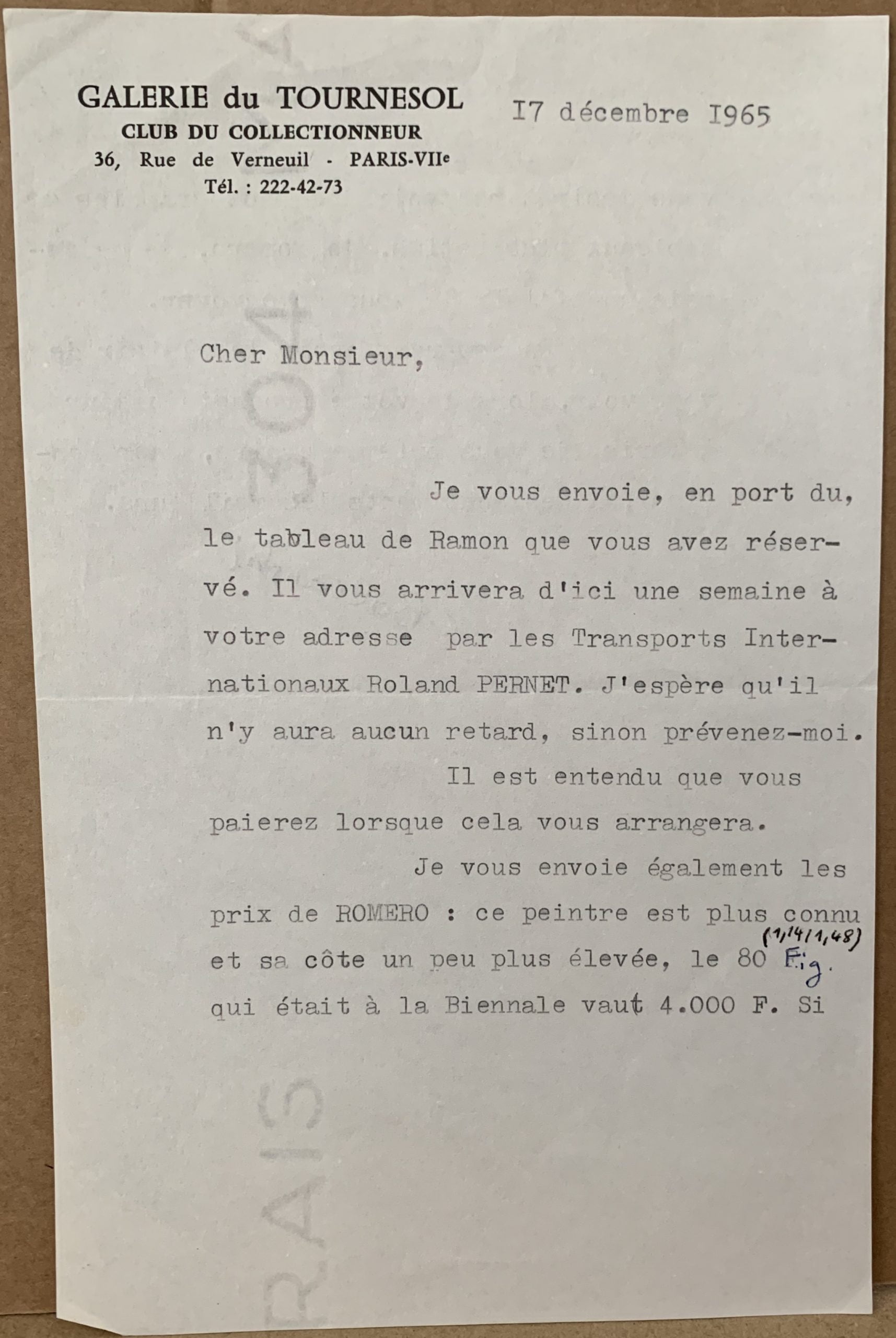

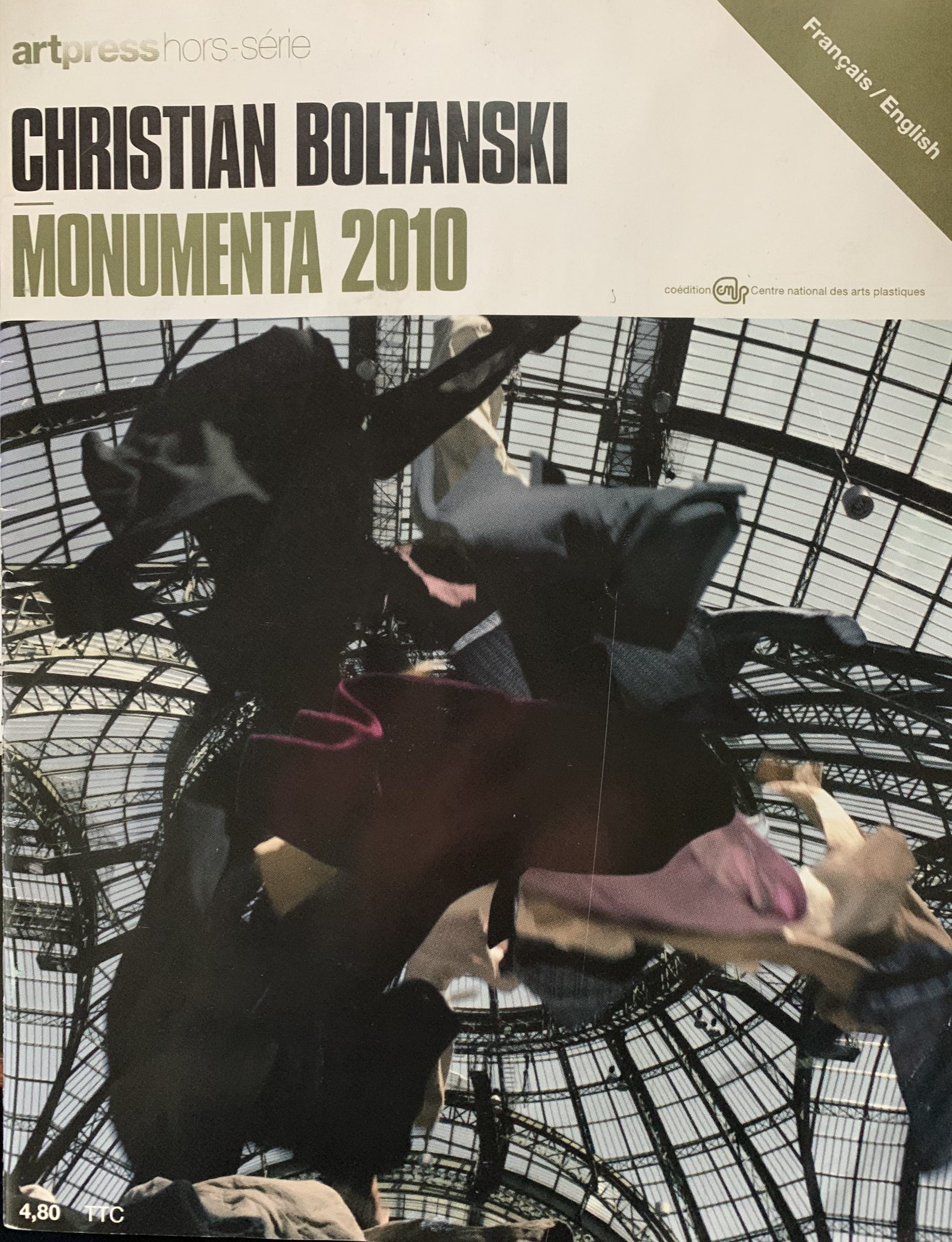

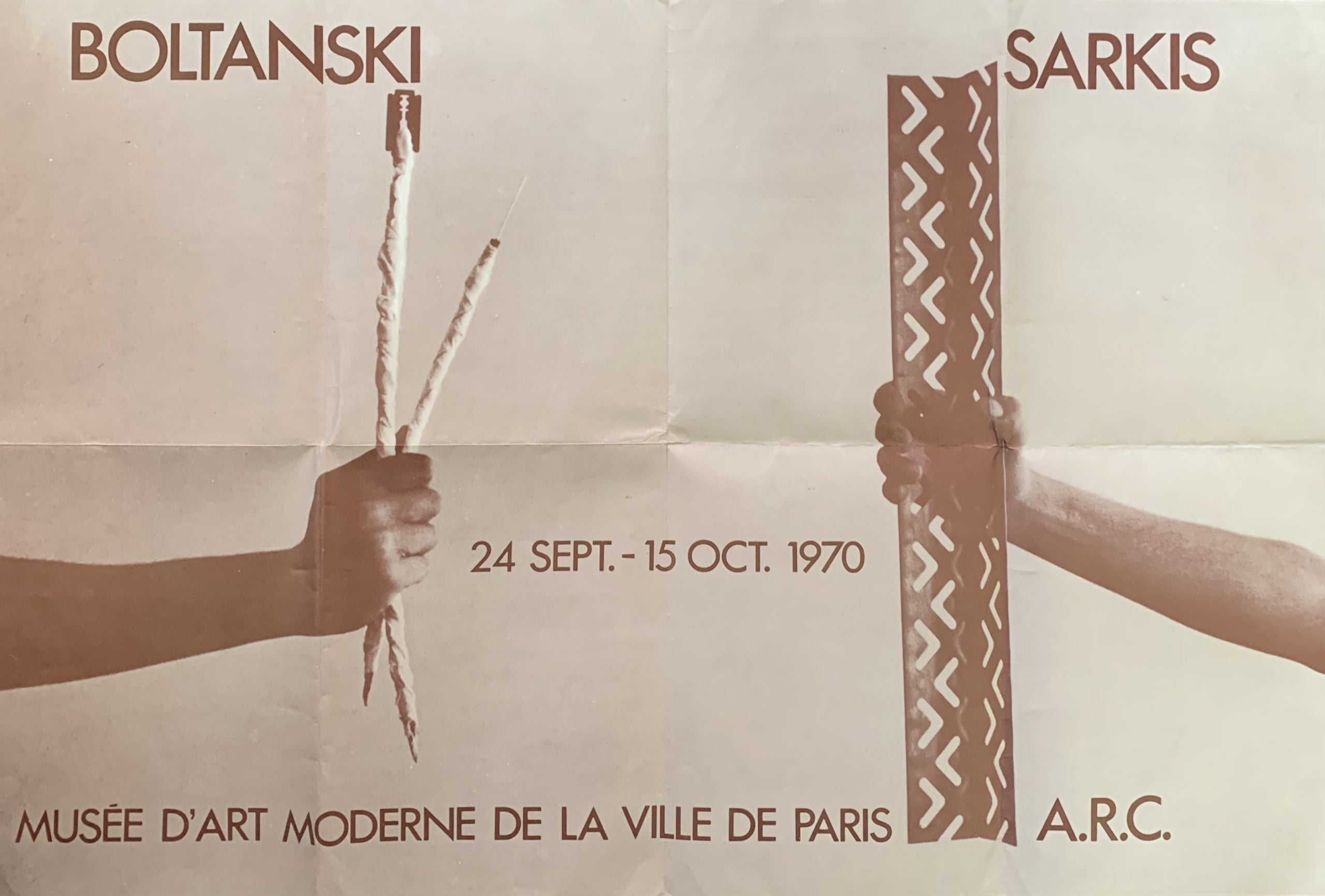

Beginning his career as a gallerist in 1967 he soon took over the programming of what was originally his mother’s gallery and made it a centre of early Parisian avant grade activity working with Sarkis, Jean Le Gac, Juan Romero and Annette Messager (who became his partner soon after their first meeting). Boltanski then began to exhibit as an artist himself (having always made “art” or rather primitive sculptures in the privacy of his own room) and found success very early on. His first exhibition was in the Cinéma Le Ranelagh Paris in 1968 but by 1970 he was showing in the ARC, Musee d’Art Modern de la Ville de Paris. There after he has had many international shows and is a major international art figure of major influence.

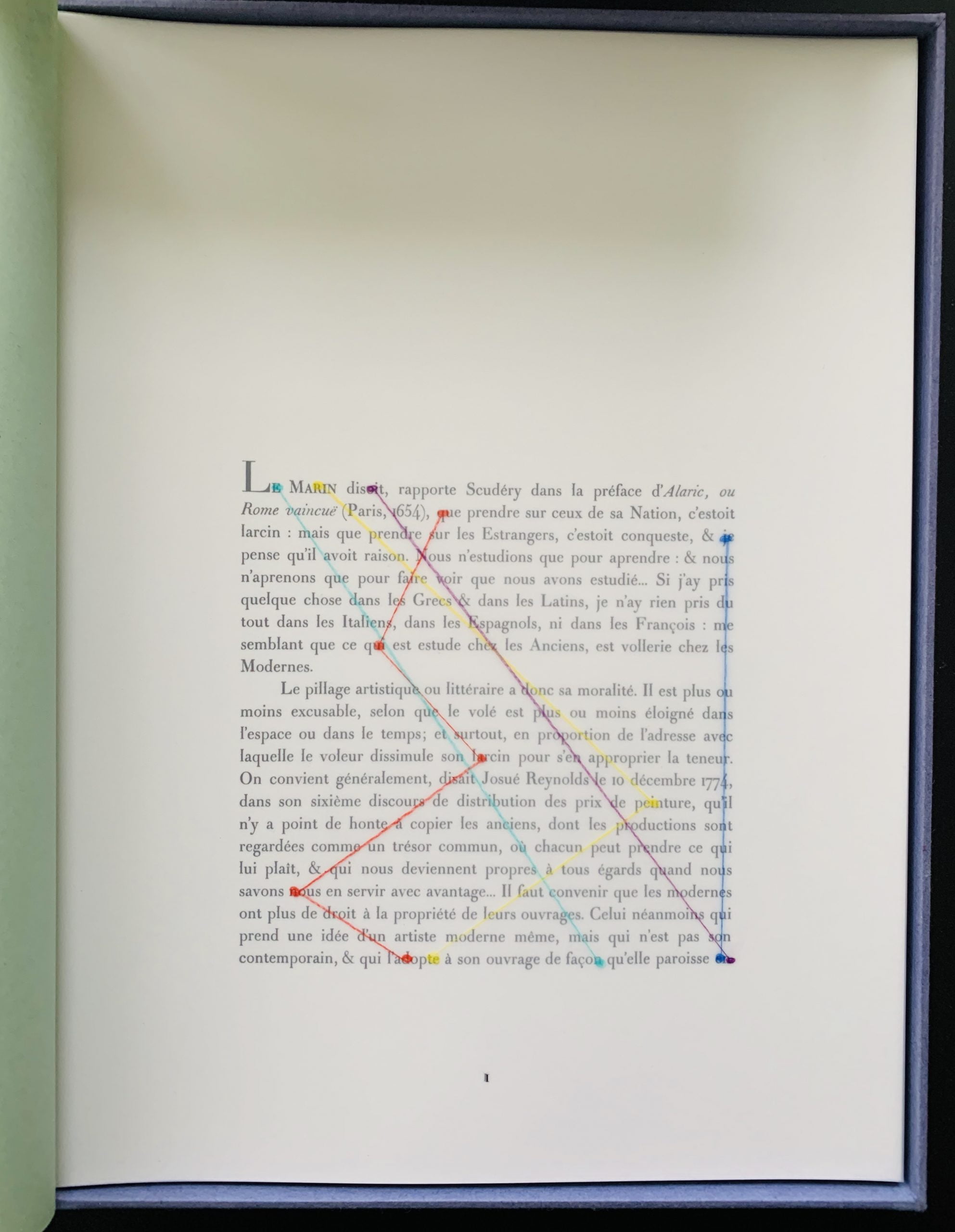

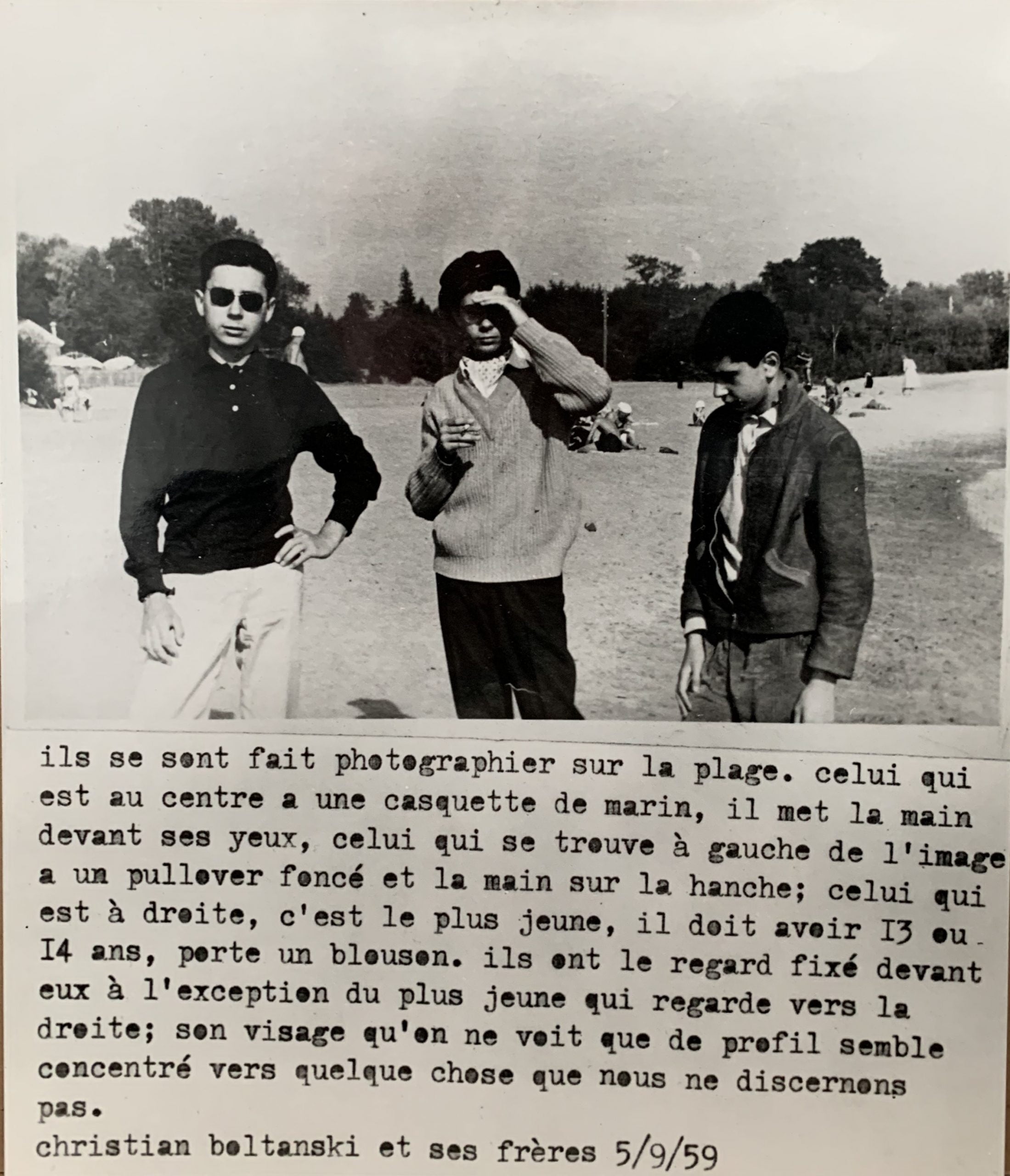

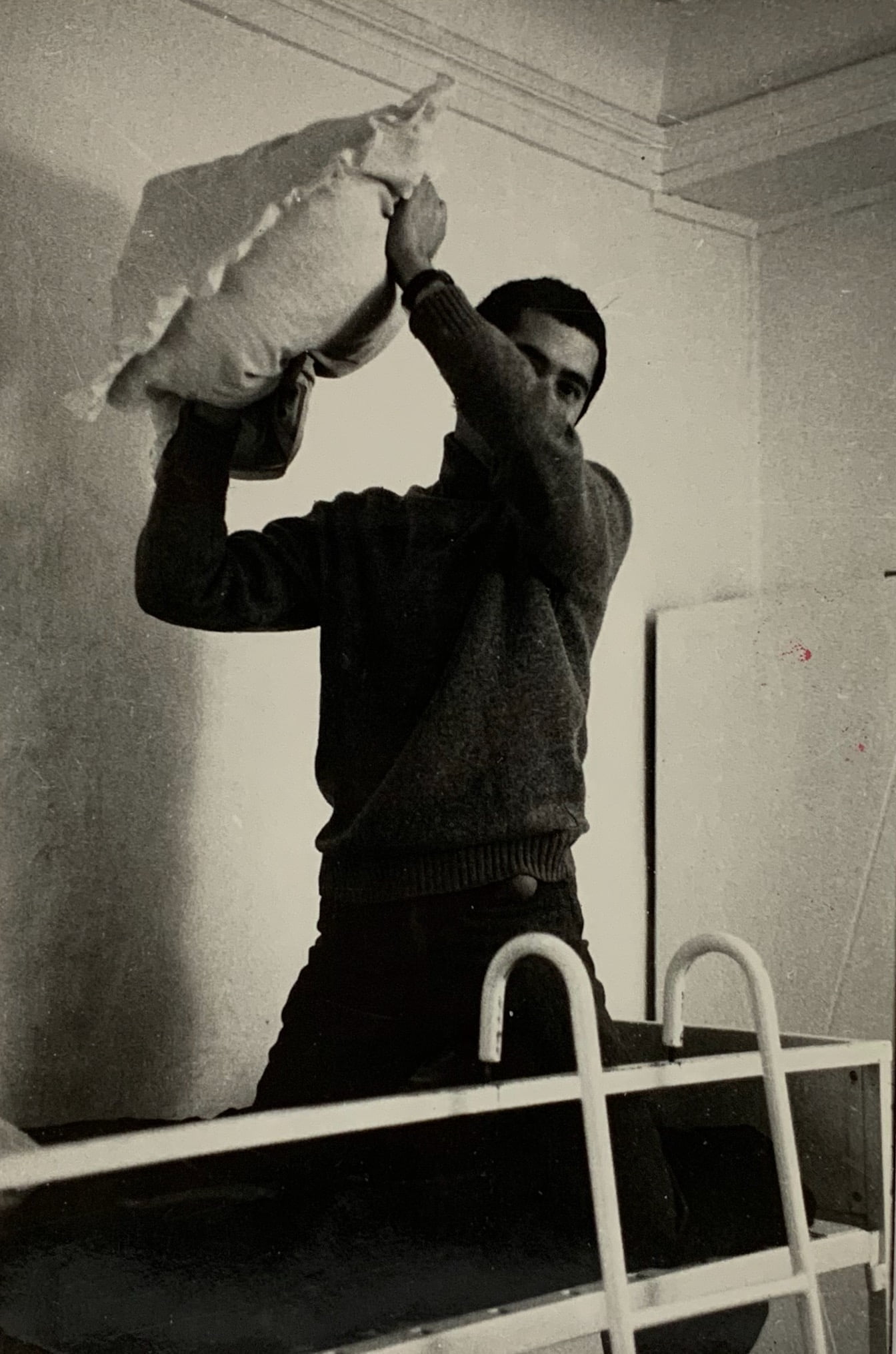

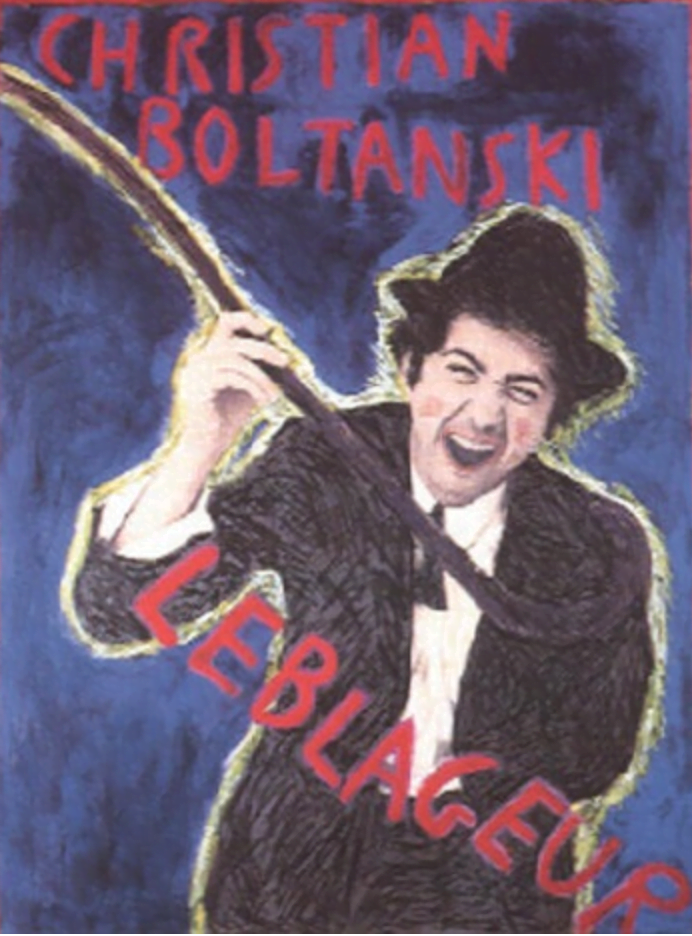

Much of Boltanski’s earliest work consisted of hand made sculptures – large numbers of roughly made knives and weapons, many many attempts at making perfect mud spheres, heaps of mud in conical shapes, human sized puppets with masks for faces but from 1968 he also made artist’s books, films and took photographs of staged performances.

An early text in his first artist’s book (ON NE REMARQUERA… 1969 – see listing) discusses his desire to create and recreate history by archiving his and other’s life but accepting the flaws caused by the failure of memory: this was a constant theme in his work from early on. It can be seen in Boltanski’s mail art and books where the images of his past life are shown but deliberately utilising other people pretending to be him or even himself pretending to be much younger. Several gatherings of all the belongings of an anonymous person shown in museum settings are also the culmination of Boltanski’s fascination with documentation but again the images shown are unreliable (the ownership not being what they claimed to be). Some commenters initially labelled this sort of work “fictionalism” but the genre title has not really stuck.

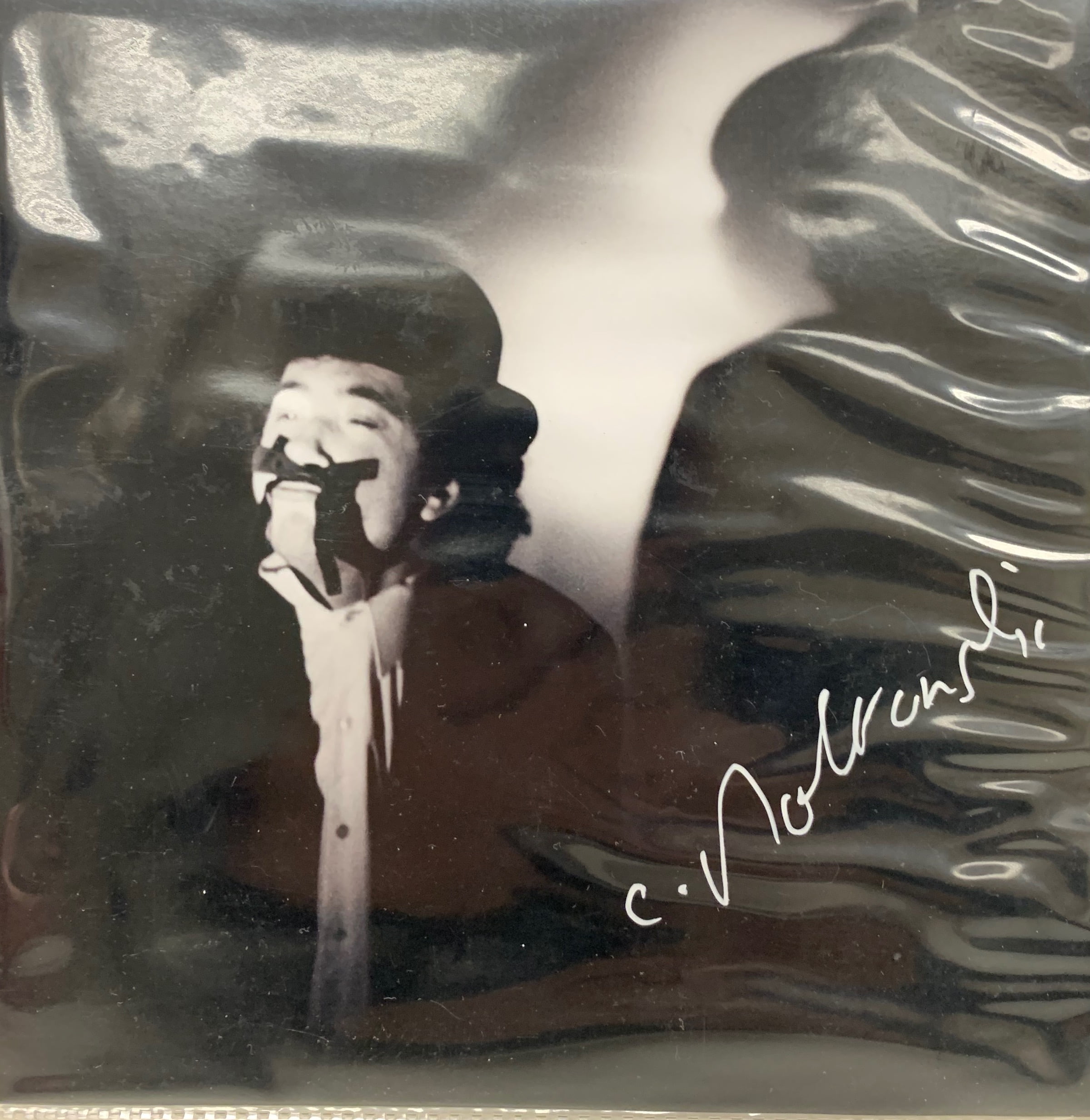

A period of live comic performances and images from them followed in the late 70s and 80s – with Boltanski taking the role of a parent figure with a ventriloquist’s dummy representing himself as a child.

Later installations were often photographic in content – daily life such as meals shown in garish detail – but also images of shadow plays and models in close up – representations of real life but still clearly fake.

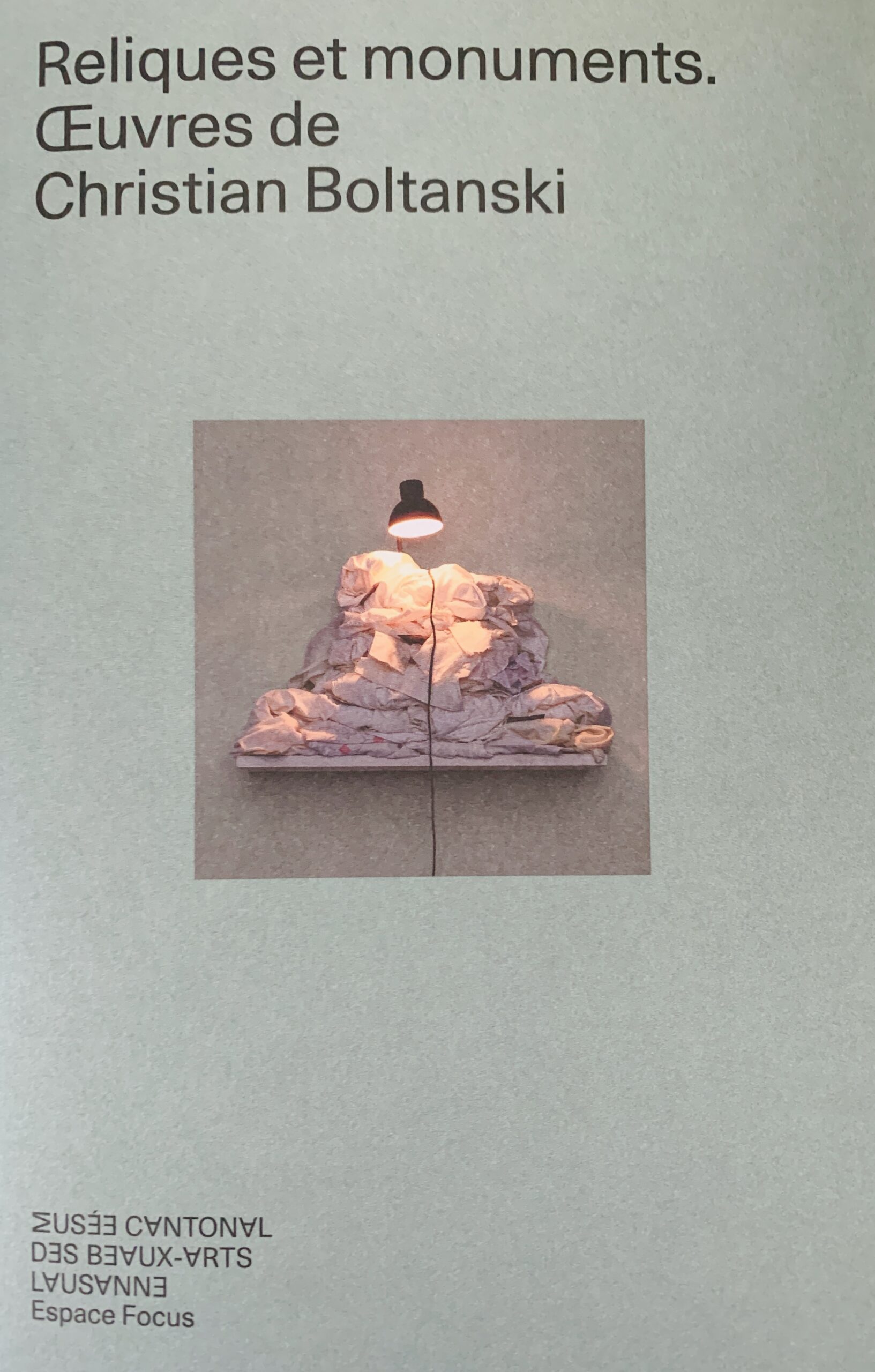

Today Boltanski is still very active and his interest in his father’s lapsed faith has become important to him although he claims not to be religious. The massacre of the Jewish people by the German Nazis has become a major area of investigation – Boltanski appears to be fascinated by the lack of evidence in some photography of the essence of the subject: murder and victim are not discernible in uncaptioned images, close ups of children’s faces do not tell you about their later fate, Nazis are shown as human beings with no evidence of guilt being apparent in the vintage documentation that the artist choses to show us. Life is like death – it is neutral – it is only society that places labels on actions.

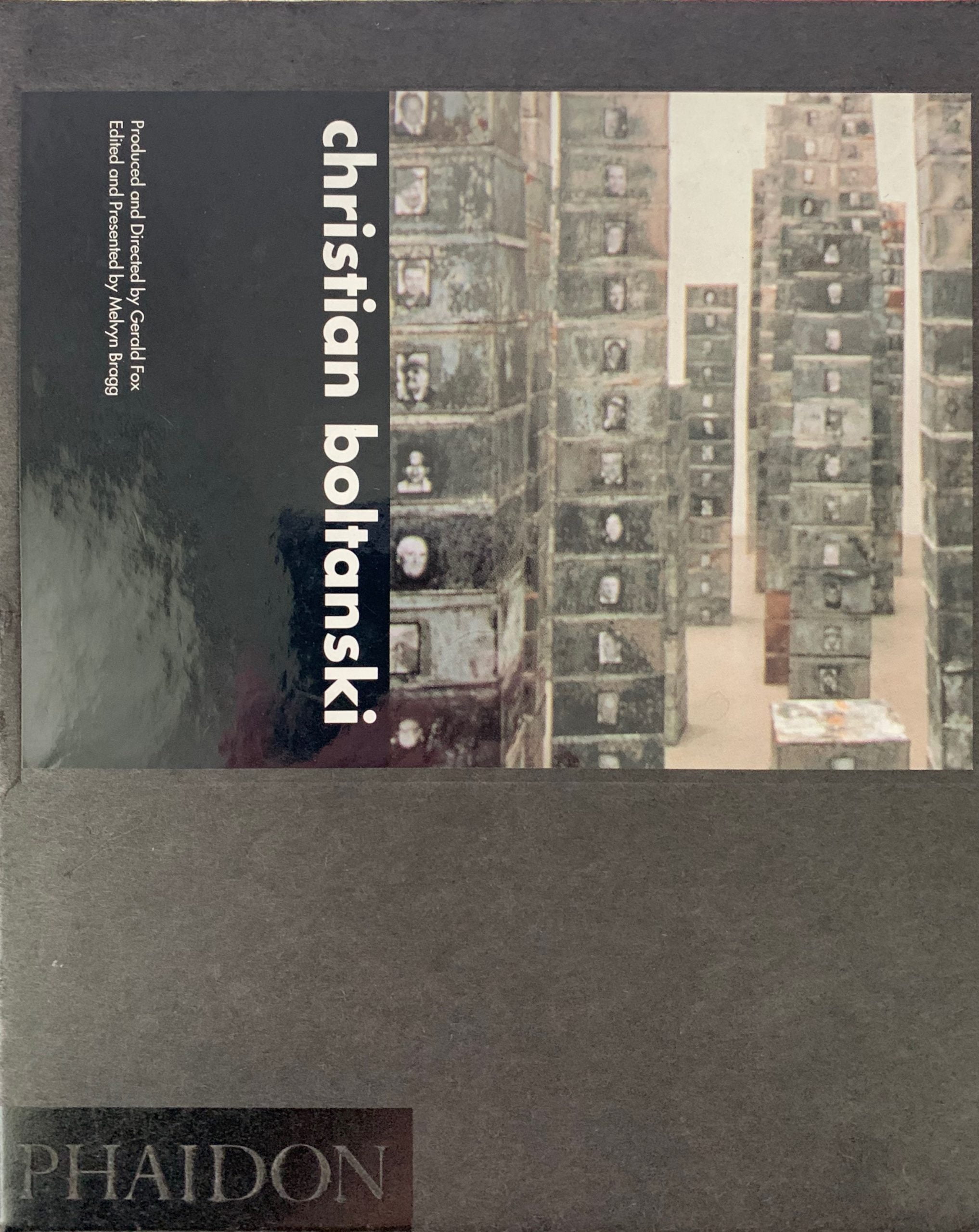

The huge installations of rusty boxes and blurred enlarged faces of the 90s again indicate the artist’s interest in memorials even if the boxes are empty and the faces unknown. This is a life’s work considering the morality of humans, their failings and their inability to change – but the artist’s eye is sometimes cold and merely a capturing of a moment without detailed evidence.

This collection was begun in 2005 by Paul Robertson and has grown to many unique works, rare object multiples, artists books (including many not known in the literature), posters, prints, records and varied ephemera, it is not for sale however under certain circumstances it may be available for exhibition. Please enquire.

Paul Robertson was pleased to meet Christian in 2016 after a number of years admiring the artist from afar. That lead to studio visits and the occasional communications between the two with Robertson sending Scottish foods and drinks as a present to the artist on his birthday which he seemingly loved.